Don't Pick on Picky Eaters

I’ve had generations of experience with what society likes to call “picky eaters.” My father had very touchy taste buds, for instance, and would carefully separate the miniscule pieces of minced onion my mother had chopped so finely into her beef stroganoff. That little pile on the side of his plate after he had finished his meal was a dead giveaway. We six children grew up knowing that dad would only eat certain foods. So when my son Zach – even as an infant – showed picky-eater tendencies, I was alarmed at first. Advice-givers, medical professionals, well-meaning relatives as well as total strangers, were everywhere. It took some research to be able to withstand the onslaught from all sides. Zach is healthy, happy and brilliant. He didn’t eat his peas. So what.

Now, as I watch my grandchildren, from ages 5 down to 6 months, I can see that t he big picky eater debate has not disappeared at all , but may have in fact, become louder in the last 38 years. I think families and societies need to stop picking on picky eaters, especially during their toddler years. I went looking for expertise on my hunch and found an October 2012 article in Paediatric Child Health , a Canadian medical journal. In “The ‘picky eater’: The toddler or preschooler who does not eat” by Alexander KC Leung, Valerie Marchand and Reginald S. Sauve, these researchers report that up to 35% of toddlers are described by their parents as poor or ‘picky’ eaters but upon closer study, these children have an appetite that is appropriate for their age and rate of growth. The authors point out several key facts to “avoid making mealtimes a daily battleground or reinforcing problematic feeding behaviors.”

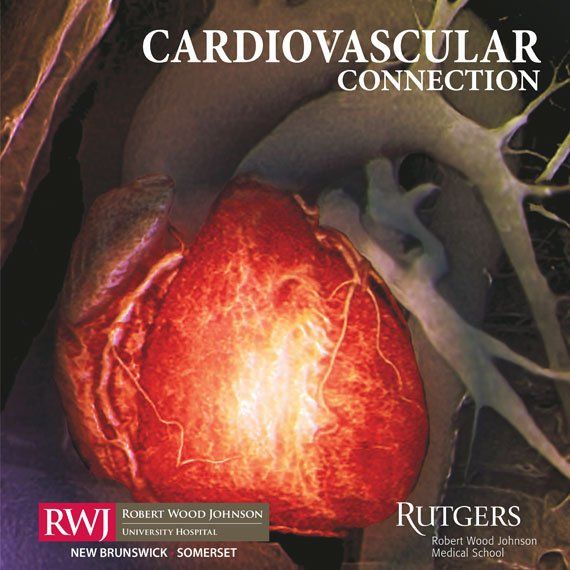

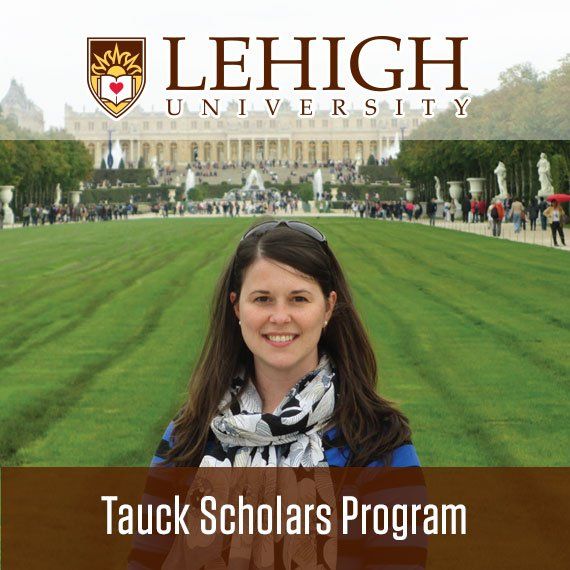

Starting with the second year of life, children all experience a decrease in appetite and their appetites are erratic from ages 1 to 5. “Young children tend to be neophobic – they do not like new foods,” Leung, Marchand and Sauve report. Toddlers are also struggling with autonomy, prefer self-feeding (to someone putting food directly into their mouths) and “become very selective in their choice of foods.” One of the more surprising bits in this article is that I think we may have child-sized portions all blown out of proportion. “A general rule of thumb is to offer one tablespoon of each food per year of the child’s age.” That translates into two tablespoons of chicken, veggies or pasta for a 2-year-old. Ahem, I know for a fact that I put more than that onto 2-year-old Evie’s plate.

Evie enjoying her little lunch!

Forcing little children to eat is a recipe for disaster. A 2002 survey of 100 college students who had experienced forced feeding as kids was so sad. These young adults remember feeling anger, fear, disgust, confusion and humiliation at the dinner table. Some had even vomited or been made to sit at the table for up to 50 minutes in stand-offs. Did being forced to eat something (vegetables, red meat or seafood) make them choose these foods freely later on in life? Hardly. In those early battles, the parent had won and the child lost. So when these children grow up and freely choose, they will be choosing to “win.” And it won't be the veggies, red meat or seafood that was forced upon them way back when.